There is a major shakeup happening in the industry, and it impacts two companies we cover at STH. Pat Gelsinger who spent 30 years at Intel, then became the President and COO of EMC, and has been the CEO of VMware since 2012, will be replacing Bob Swan as the CEO of Intel. This is a big deal.

Pat Gelsinger Next CEO of Intel

On February 15, 2021, Pat Gelsinger will become the new CEO of Intel. The Intel board saw the need to change an industry narrative where customers were turning on Intel. On the consumer side, Apple issued its declaration of independence in terms of its M1 Arm-based CPU. AWS, Google, Microsoft, Oracle, and others are deploying AMD and Arm CPUs in their data centers. While insatiable market demand for compute as the new currency of industrial might has led to great financial performance, at some point, Intel needs to change the narrative from being the beneficiary of a rising tide lifting all ships.

One of the biggest challenges at Intel is its past success. Intel became so dominant in desktop and server markets with market share in the high 90% range, that it had limited competition. We focus on the server segments but there IBM Power is very cool, but IBM could not ignite a spark that would take it out of that single-digit server market share realm. AMD was effectively one failed product launch away from having to re-evaluate its role in the CPU market before Zen. AMD’s product concept was wise given that it was launching a solid product at a time when Intel’s process technology went from leading at 14nm to behind just trying to get 10nm out in quantity. Without 10nm, Intel could not deliver PCIe Gen4 servers. Without PCIe Gen4 servers, it did not have a market for its PCIe Gen4 SSDs, network adapters, AI accelerators, and other products.

At Intel, it had fallen into a common trap. As a company gets larger and sees success, more of the revenue comes from traditional lines of business. If you have a $1B product line in a non-competitive market, such as the server market had been from 2013-2019 or so, raising prices to existing customers by 10% is an easier way to get $100M of incremental (mostly margin) than building a new $100M product line from scratch. In consulting, we used to call the teams that worked at the same big customers “farmers” because they would work almost exclusively on the same account for years.

Hunters on the other hand were folks that went out and sold new types of projects and to new clients. In my consulting career, I spent much of my senior associate days as a farmer, but by the time I made director, all I wanted to do was to be a hunter and sell new products to clients that often used other consulting firms. Hunting is hard because one expends significantly more effort chasing smaller dollars which means to hit my sales targets I had to work on new offerings and find new customers often pitching against incumbent providers or to startups that had never purchased management consulting services. I still would hit my annual sales targets within 3-4 months, but there is always a sense of insecurity having to wake up and hunt in the market versus knowing you had a stable client. Selling even just $5M in consulting work often meant a large number of pitches and constant innovation to win relatively smaller deals that one would hopefully lead to a client becoming a longer-term client. Selling Core and Xeon x86 is not hunting, it is farming. XPU is hunting. As an example, Intel Xe, the company’s GPU efforts, is going after a market segment dominated by NVIDIA and AMD.

Perhaps the biggest question is how Pat will demonstrate that he is still a hunter, rather than a farmer. Over the past seven or so years, Intel became so dominant in x86 that when its process leadership failed the product side, and the product leadership did not adapt quickly, it started a cycle of disruption that has allowed AMD on the desktop and server-side, and Arm architectures to get footholds in the market. Intel became complacent as it effectively had a monopoly in the server and desktop space for years.

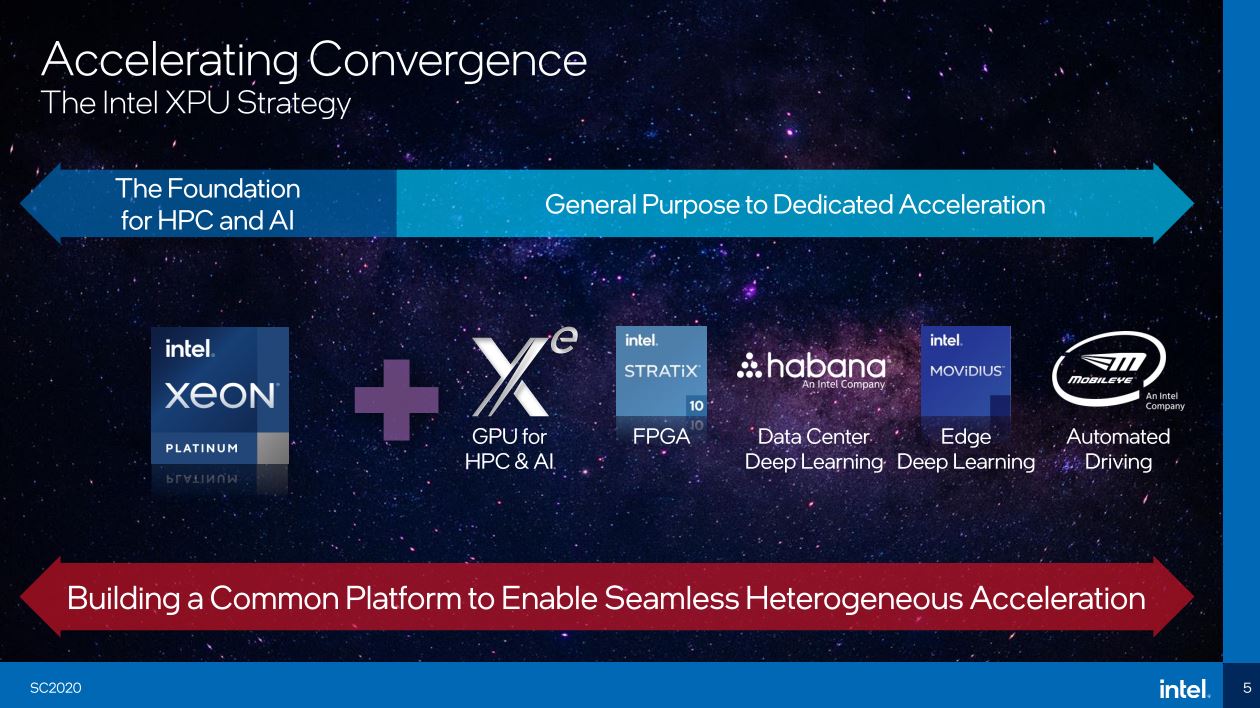

The 10nm delays, pushing the Ice Lake Xeon series to the point where it is news that they are now in production in 2021 instead of launching in 2019 has forced Intel into an unfamiliar space, the company needs to transform back from farming a customer base to again proving that it can deliver industry-leading innovation. Intel has set the path of innovation away from the CPU and to the vision of an “XPU”. With XPUs, Intel can move into new spaces such as GPUs, AI accelerators, and customized solutions with modular IP blocks. This is the right model for Intel’s future. The XPU focus acknowledges that moving to new segments increases its silicon TAM while also offering a wider range of competitors.

Challenges at Intel today mirror what happened at VMware. VMware was a clear pioneer in virtualization. These days, the large virtualization players most likely do not use VMware. Public cloud providers are not running atop of ESXi. Instead, they are using KVM virtualization. VMware-focused professionals still extol the virtues of VMware, but the cloud providers and even the Open Stack community has changed the market, similar to what Intel is experiencing.

Losing in its traditional market of virtualization, Pat and the VMware team recognized this was inevitable and moved to other market segments. For storage, we got vSAN even though that, in many ways, put the company in competition with EMC. While it would compete with EMC, vSAN allows VMware to compete with Nutanix, Microsoft, and others. For networking, the 2012 Nicira acquisition allowed VMware to add a network virtualization component and NSX. This led to VMware competing with many of the networking hardware and software vendors by changing where the center of networking and control logic resides.

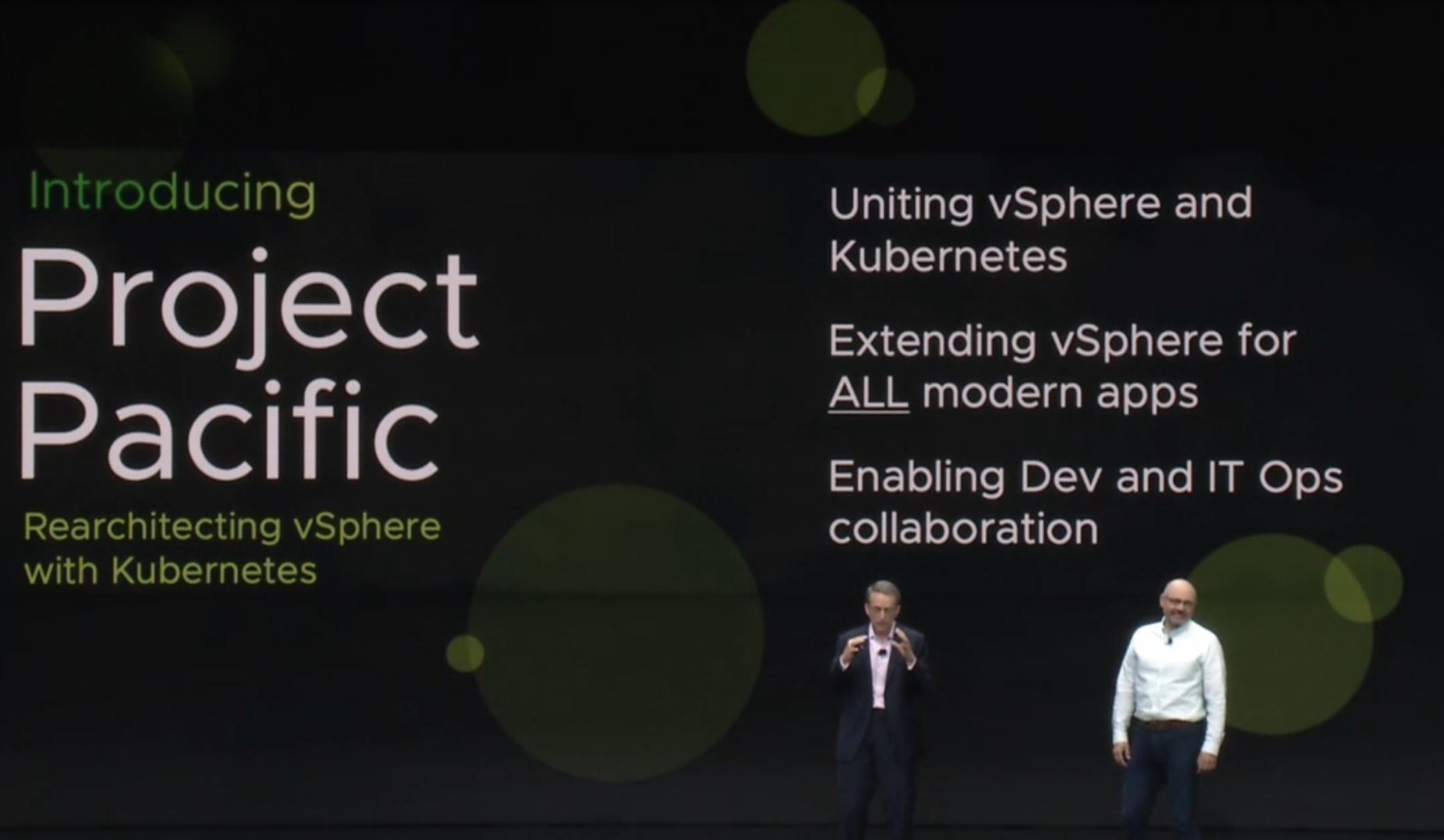

VMware was not early to Kubernetes, Project Pacific/ VMware Tanzu is the company’s offering that arrives after much of the industry had already deployed the new standard. VMware needed to build an offering here in order to ensure its lucrative enterprise customers did not need to reduce their VMware server counts as workloads shifted from virtual machines.

While VMware lost an enormous amount of virtualization market share, the company has innovated either internally or through acquisition to expand to adjacent markets. VMware’s new paying customer sign-ups are not as numerous as some of the big cloud players, but by offering a more complete stack, it can remain relevant for its enterprise customers.

That strategy at VMware aligns nicely with Intel’s XPU efforts. With XPU, the company may lose x86 market share. It may lose share in desktops and servers, but the company’s fortunes lie in embracing the disruptors and offering high-value silicon solutions going after product segments that are new or that were previous adjacencies.

Final Words

Intel as a company and the industry context dictates that there are only a handful of people that could assume the role of Intel’s chief and have a reasonable chance at success. Pat Gelsinger with his long history at Intel, along with the relationships he has built with Intel’s major customers at VMware mean he is on that shortlist of folks, and perhaps the top outside candidate.

We are seeing Intel move to its XPU strategy as an example of the company moving from farming its existing customer base to hunting new markets. The question now is what changes Pat will make to transition this farming culture to a hunting culture. Intel is large enough that it needs a mix of farmers and hunters, but it is clearly in need of changing that mix.

Congratulations to Pat on this personal milestone. There are very few people who start working at a company like Intel as a teenager, spend 30 years there, and do not at some point have dreams of becoming its CEO. As great as EMC, Dell Technologies, and VMware has been, we need to take a moment and recognize on a personal level this is someone achieving a dream.

VMware is playing a losing strategy in the long run and will become a bit part player in the scheme of things.

Intel might be better placed to adapt due to the high barriers to entry in the chip market.

Maybe I am too cynical, but I thought for a long time that VMware and Pivotal were just pawns in a game.of financial and psychological.manipulation. Companies based in Texas (Dell) and Massachusetts (EMC) want to paint on a little San Francisco to impress customers and investors. In that case somebody has to be a CEO but iwhat does he really do?

There might be no reason for a company to exist so far as business is concerned (hypervisors are a kernel thing) but if you can manage to hold a public company listing that is literally a license to print money; people see a vmware logo on CNBC and assume therr is something there and everybody invests in index funds so ut doesnt matter if there is any there there.

Past that there are people in businexs who are terrified of open source software and either need proprietary software to banish it (vmware) or some hand holding (pivotal) — Pat has some experience in managing decline but Intel doesnt need ‘relationships’ it needs results.

Mr Gelsinger was offered the Intel job once before and turned it down.

What made him accept it this time?

Intel also has an activist saying they should outsource fabs. I think Intel needs these:

1. There’s a shortage of global semiconductor fabrication capacity and Intel should offer more contract fabrication and be additive not subtractive to global capacity. For Intel, that’re a pure farmers market that hasn’t even been started…

2. It needs to get ahead of its 10nm and 7nm production woes, but Patrick may shine some light: whats the status of Intel & EUV vs TSMC/Samsung & EUV? If they’ve managed to get EUV working and the others haven’t, then the delay is investment in the future.

3. It is already on the right path with the Xe graphics to take on AI and Nvidia and AMD in GPUs. Arguably, however, Nvidia leads because of their software, such as CUDA and better drivers. Intel’s software outside of compilers is often lacking.

4. But it’s sorely lacking in networking IP. It has the building blocks in its acquisition of QLogic, Infineon, Lantiq, Xylinx and its own network business but it hasn’t focused sufficiently to make DPUs like Amazon’s nitro or Mellanox’s (Nvidia) ConnectX.

5. Intel has a tendency to go after whole industries and failing. Mobileye is all about ADAS and self driving cars, and Intel sees the entire pudding, not part of it. It has fingers in so many pies and tries to dominate all, but instead it needs to do what VMWare has done with the ancillary industries and specialise in a few areas well. For example, the software router market is dominated by quite poor SD-WAN solutions, the best of which use DPDK and VPP – both Intel creations. Yet Intel doesn’t have a turnkey software router leveraging that… they keep doing all the hard work on architecture but never the actual nugget of an end product that people need!

6. X86 instruction set needs rationalising. It’d be better to put ancient variable length instructions from 386/486 days to a dedicated core/block and focus the main CPUs on fixed length instruction processing. This will ensure the complexity of CISC instructions are reduced, with knock-on simplification of the chips, and yield greater speed (ie what Apple’s M1 has achieved). Sure it may involve a little more compiler complication effectively having a coprocessor for junk instructions few use, but that’s a problem that can be solved with silicon and a bus.

7. Beyond that, the X86 wider ISA (that is PCIe lanes, memory and so forth) are all on different buses. With their leadership in CXL or something similar, Intel could force a unified bus for all memory, DPU, CPU, GPU and interconnect, which effectively means the motherboard just becomes a huge bus and switch with interconnects, and you just slot in whatever you want, transputer style. In addition, Intel should reduce the cost of Optane dramatically and just make non-volatile memory as the only storage necessary for a compute platform.

I liked the farmer/hunter analogy for Intel salespeople. I worked at a large storage vendor in the ’90s. They had grown from nothing in the ’80s to a major force, and had done it entirely with Intel microcontrollers. Our Intel sales rep had grown with the company to the point that our company was his only customer and as the article say he was just “farming” us. Supposedly his commissions were so large that he had a yacht parked out in the local harbor. We engineers, on the other hand, hardly ever saw him.

The storage company I worked at still exists, but they long ago switched away from Intel microcontrollers and Intel hasn’t been a force in that market for a long, long time.