This week, Supermicro put out its second annual Supermicro Data Centers & the Environment Report. In the report, the company makes a few key points revolving around how data centers can be more environmentally friendly. It also presents the survey results of how data centers are being run today. I had the opportunity to review a draft of the report and wanted to call out a few points for our readers. The report itself is worth a read, but I wanted to pull some thoughts together after reading the report.

Whose Problem is the Green Data Center?

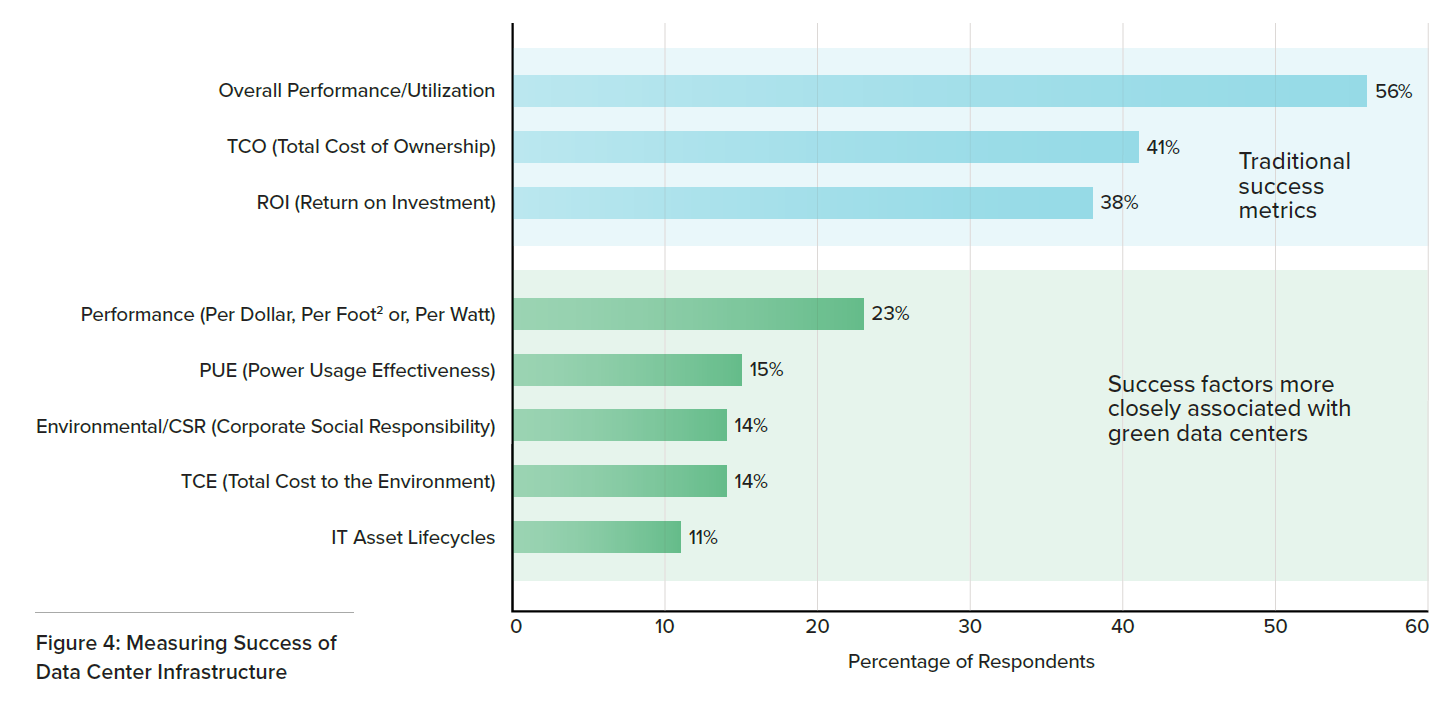

On Page 4 of Supermicro’s report, one has the survey results of how respondents measure data center infrastructure success.

The survey’s results show that metrics such as TCO and ROI are the key drivers. This makes a lot of sense because corporate planning, budgeting, and operations. Traditional success factors are the ones that drive the financial performance of companies.

Supermicro offers a number of fairly standard ways to alternatively measure efficiency. The fact that so few respondents mentioned these is interesting in itself. My thesis is that it is because those metrics lack a distinct owner.

Today, large data center operators offer colocation services for a myriad of businesses. It is not uncommon to see a data center with cages used by many large enterprises next to one another. Maintaining shared facilities versus operating private data centers has a number of advantages and that is why the market has been moving this direction.

In that example, who owns the responsibility of the PUE for the data center? Is it Equinix serving as a landlord, but not making decisions about its tenants’ equipment within? Is it the tenants who make equipment decisions, but do not control the facilities? More challenging is it the responsibility of companies like Supermicro to make their gear as efficient as possible without controlling how or where it is deployed.

For large organizations that control the hardware and facilities such as hyper-scalers like Facebook and large companies like Intel, they can unilaterally move the needle on this. For many server deployments, environmental metrics are hard to impact.

The correct question seems to be whether that is the right way to operate. We know data centers consume a lot of energy and generate heat. At some point, the industry needs to come to terms with the sustainability issue. That will only happen when CIOs lead environmentally forward-thinking campaigns. If you want to outline a leading IT platform in 2020, finding ways to cost-effectively increase data center IT efficiency should be part of a multi-year program that can be rolled into corporate responsibility discussions.

Higher Temperatures and Efficient Operations

Another key thesis of the article is that consolidating to multi-node platforms that are partially refreshed on regular cadence is more efficient. On some level, we expect a company like Supermicro to advocate more frequent refreshes.

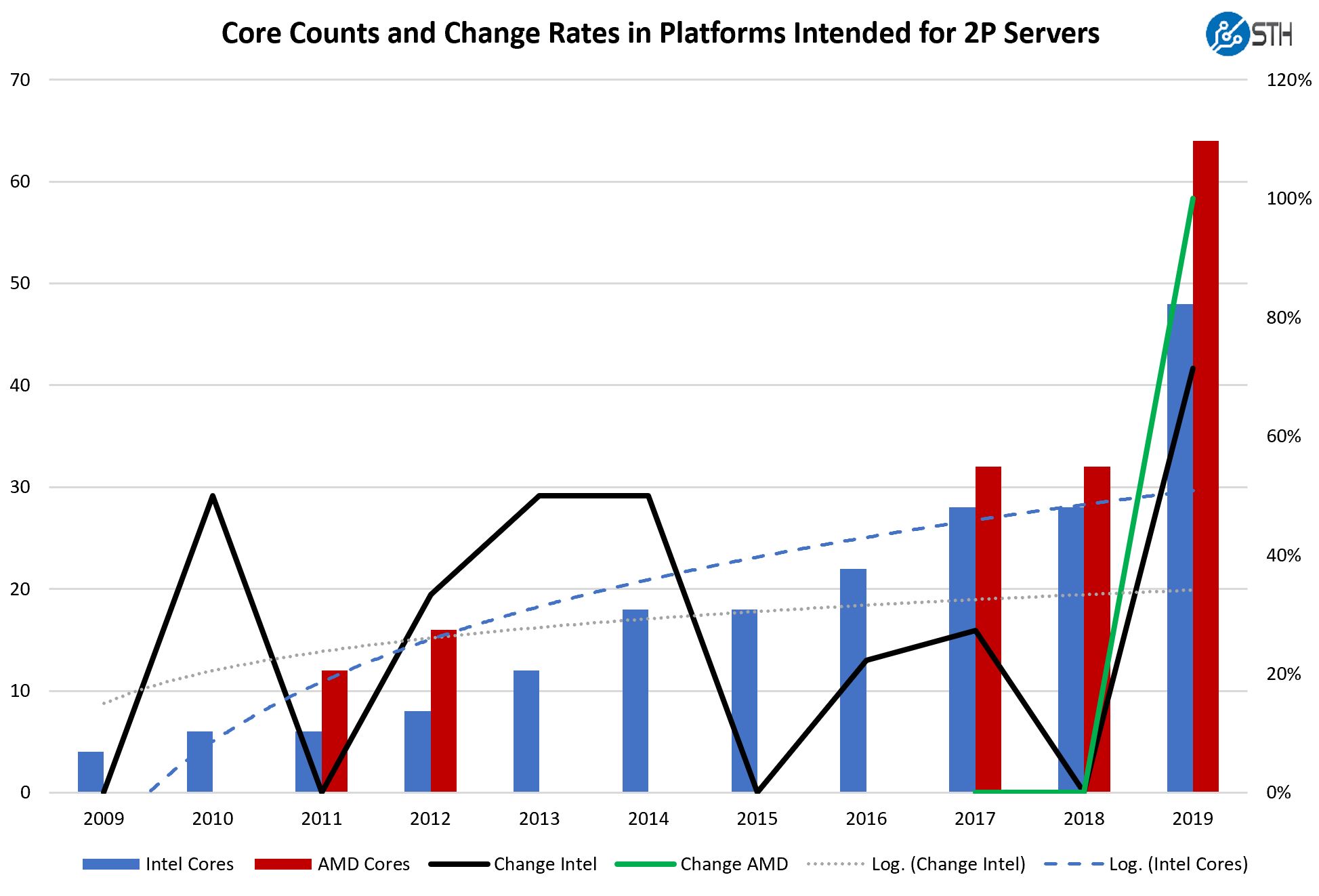

In 2019 and 2020, the notion of refreshing for efficiency is a lot different than what we saw in 2016-2017. Core counts in servers have risen at a rate that we have not seen in a decade.

As you can see, the 2018 to 2019 delta is so far away from the logarithmic trendline over the last decade that the idea of consolidating for more efficient operations is attractive for the first time in years. The last time we saw this big of a jump was in the 2012-2014 timeframe with the early Xeon E5 series. Competition in the market means that the relatively mundane days of 2014-2018 IT are over. We are now facing the prospect of 4:1 to 8:1 socket consolidation ratios over three-year-old servers.

To aid in that process, Supermicro is also suggesting that switching to modular servers makes sense. These can be the company’s 2U 4-node (e.g. Supermicro BigTwin SYS-2029BZ-HNR) and blade servers for example.

Key here is that the sheet metal, fans, and power supplies have such long service lifetimes these days that they can be used long after the servers in them would be replaced. Not only does that save on direct materials, but it also saves on shipping and labor to replace the chassis.

There are a few caveats here. First, the CPUs and GPUs we will see later in 2020 and beyond will use more power. Higher power CPUs using the same fans may not be the best fit. Also, backplanes need to support PCIe Gen4 today and in 2020 and we will start looking at PCIe Gen5 from 2021 to 2022. Still, there is a case to be made that this can result in massive operational savings.

To get there, we think that Supermicro will need to offer attractive pricing on refresh servers. If one wants to purchase new nodes for existing chassis, the discount that entails should be part of the initial sales process in a way it is not today.

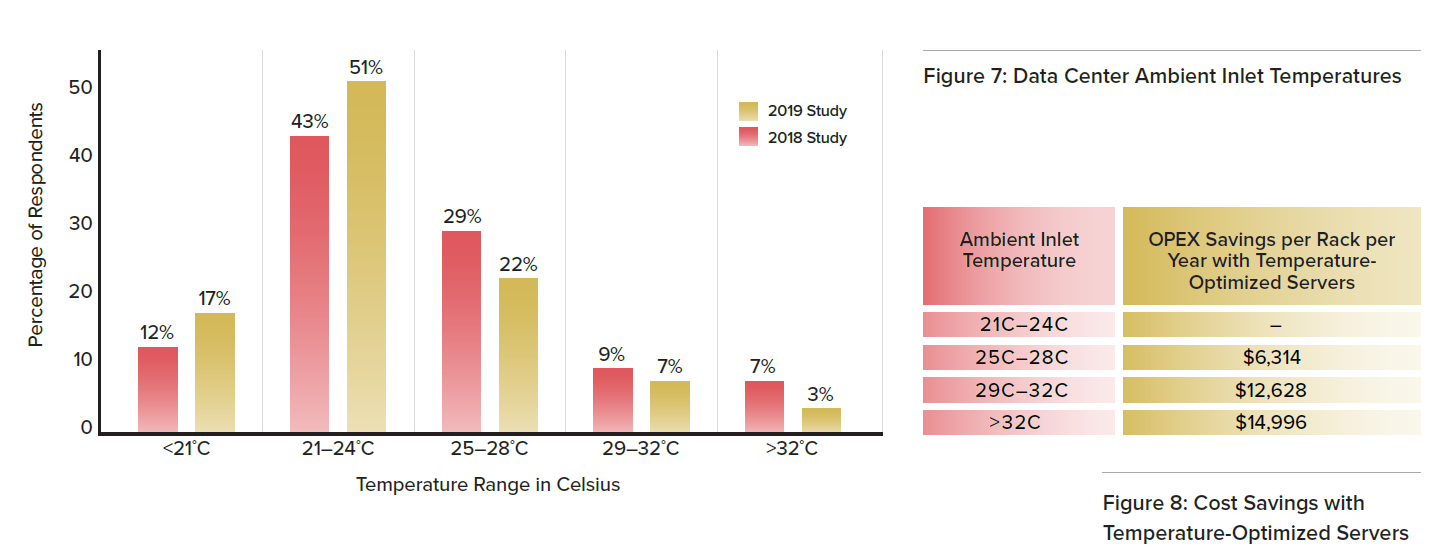

Supermicro also focuses on how running higher ambient inlet temperatures can lead to lower costs. When we looked inside Intel’s 1.06 PUE Santa Clara data center and when one looks to examples like Facebook‘s Prineville 1.07 PUE data center, they are using a lot of ambient cooling and tolerating larger temperature ranges than traditional data centers. When Supermicro looked at this trend, it found something different:

In 2019, fewer respondents were running higher temperature data centers, instead of focusing on more cooling. Newer servers are generally designed to operate at higher temperatures so this is another source of potential energy and OPEX savings.

As a quick aside, not all hyper-scale outfits operate like Facebook with this goal of environmental responsibility. Some large cloud providers use smaller and less efficient facilities and focus on offsetting energy consumption by using renewable sources. You may not care when you spin up an instance, but perhaps you should.

Final Words

The discussion of data center efficiency is important. On one hand, we can look at infrastructure as a simple set of CAPEX and OPEX related decisions. That is business as usual and will be the way most businesses look at the segment. Employee performance plans are driven around CAPEX and OPEX goals and those goals drive human nature.

Perhaps the most striking part of the Supermicro report is not just the report itself. Instead, it is the sense that, as an industry, we need more CIOs to take up the mantle of corporate responsibility and create actionable long-term environmentally-conscious plans for their organizations. Hopefully, by 2025 we are judging CIOs not just by how they manage CAPEX and OPEX but instead about how they managed to achieve those numbers.

Supermicro, frankly, does not have all of the answers to green IT. It offers a viewpoint, but it takes an ecosystem of providers and customers to move the needle. As one of the world’s most technologically advanced industries, how should be important, just like the result.

Quick Citation Note

Keen readers will notice on Footnote 3 that our Supermicro BigTwin NVMe Review was cited for testing individual 1U server versus shared chassis 2U4N designs. It is always great to see our work cited.

Why does the intel bar for corecount show as around 48c in 2019? To my knowledge, production chips for cooperlake dont actually exist in a form I’d consider production yet – and it certainly hasn’t been released to the general public. There are definitely samples that some Tier1s have, but I’ve only heard that they have ES chips at this time. Also cooperlake has 56c SKUs planned for the scalable processor lineup in its latest incarnation.

If that bar was meant to be cascadelake advanced processor lineup, it would be 56, but those aren’t remotely mainstream 2s platform chips to begin with either.

Hi Syr, that is Cascade-AP. I agree with you. There is a version of that chart tagged mainstream that was in an earlier draft.

The way datacenters are built doesn’t really help matters any. Look at cooling as one example. The typical datacenter is built by contracting with a builder, who in turn subcontracts with a mechanical firm. That firm uses whatever solution they always use. And it’s usually not an efficient one.

There’s not a lot of room in the process for swaying the contractor and subcontractor towards a more efficient solution, especially if it means using equipment from a vendor they don’t do business with, or requires engineering a solution they haven’t engineered 100 times before.

The consequences of this “contractor as decision maker” build-out model, is you commonly see far less efficient technologies deployed, which cost roughly the same as the more efficient options. In cooling in particular this makes a huge difference, as there is perfectly good indirect-evaporative-cooling systems from Excool and others that can do a 1.10 PUE even in Phoenix, AZ, versus a more typical CRAC + Raised Floor + Chiller configuration which gets you anywhere from 1.3 to 2.0 PUE. Strangely, these less efficient options often cost more and take up more floorspace, in addition to being less efficient.

Being in a process of building out my first datacenter right now, I can say I was very surprised to learn how the industry operates. Speaking with people who’ve built datacenters in my area, I find my experience to be typical, sadly. The standard process seems to revolve around shopping around for a contractor rather than shopping around for the best equipment to build your datacenter with.

This article points out a problem where the primary concerns are TCO / ROI / and overall performance, and that build decisions are driven by that. I wish that was true! The real state of things is far worse than that.