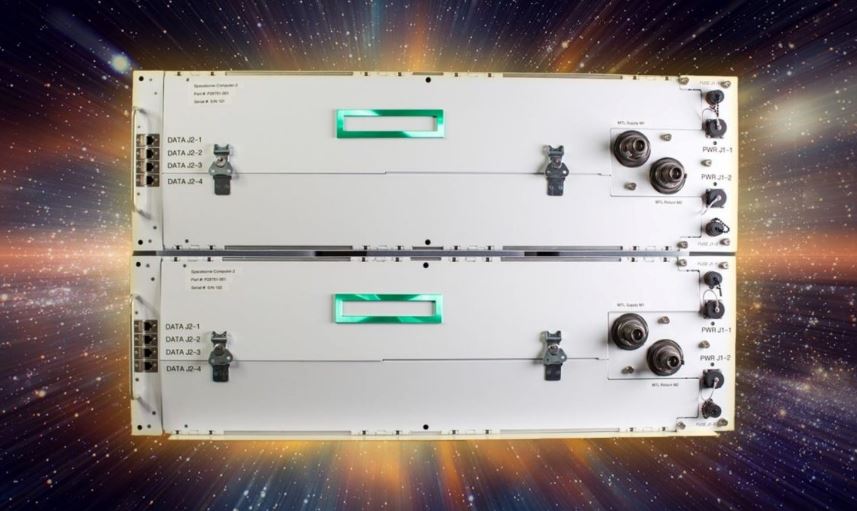

This week, HPE announced that its next-generation outer space server is launching upon a Northrop Grumman rocket. Dubbed the HPE Spaceborne Computer-2 system, we did not have any great photos of the new system, so instead, I went back in the STH archives and found some older photos of the original Spaceborne (1) system that HPE showed me at HPE Discover 2019.

The Original HPE Spaceborne Supercomputer

We did not run the story back in 2019 because of two factors: the SD card in the main camera was corrupt so we lost the stills before I got back to the hotel room in Las Vegas and could make a backup copy. Second, I recorded a video and just behind me, a gentleman started playing a music set on his guitar which was picked up (clearly) by both microphones. So instead, I grabbed a few stills from the video since I realized this is not shown off often.

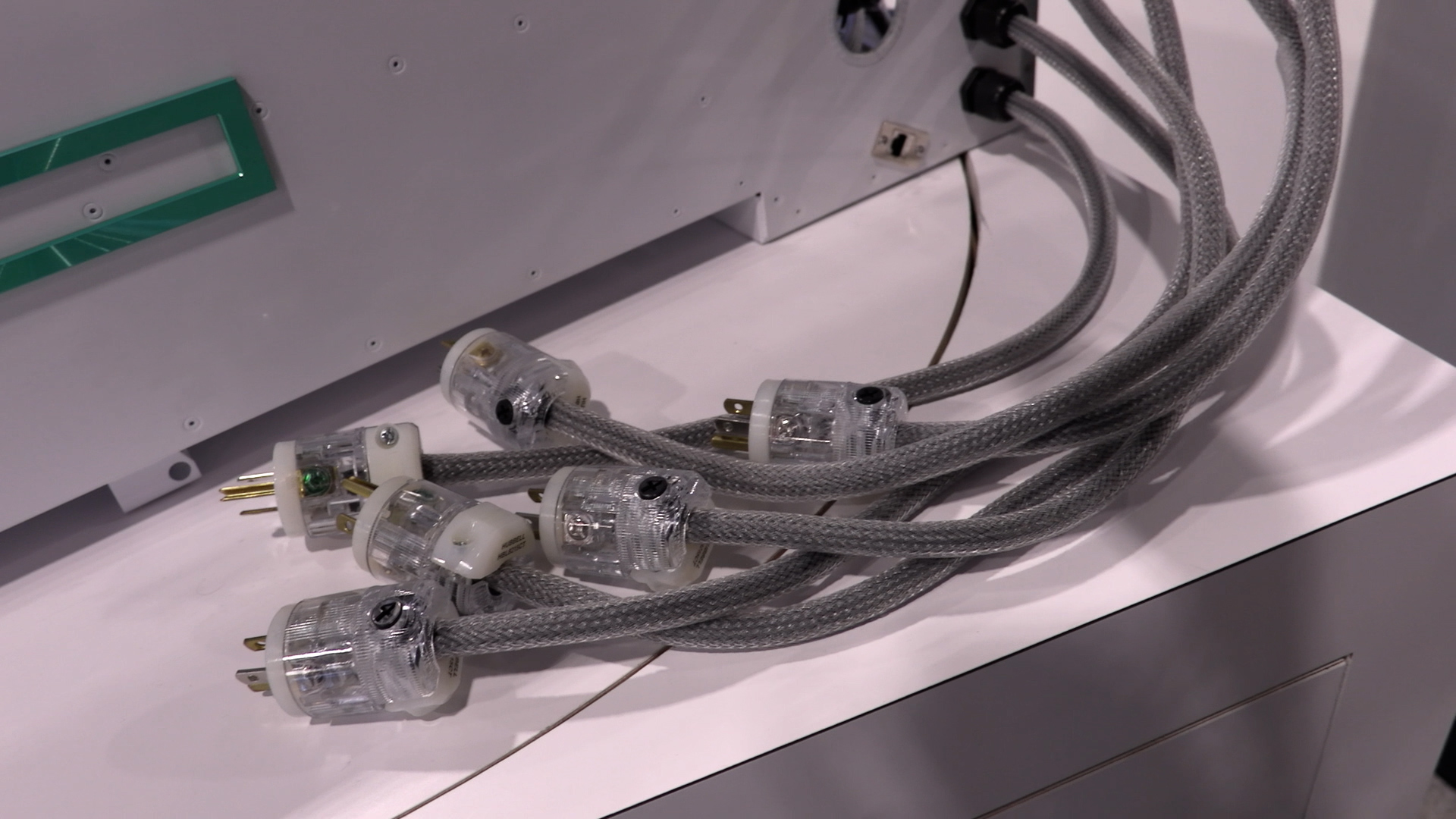

First off, one can see the big cable array coming out of the system. These may look like standard North American 120V prongs at the end of some fancy cables. Indeed, that is what they are, albeit in fancier cables than we typically see on standard servers. Something that I thought was interesting here was that one has to remember that in a launch there are high forces at play, but it is also expensive to launch each kg of payload (the first HPE Spaceborne computer launched atop a SpaceX platform.) That must make for an interesting launch cable packaging so that these connectors are not vibrating and hitting other equipment.

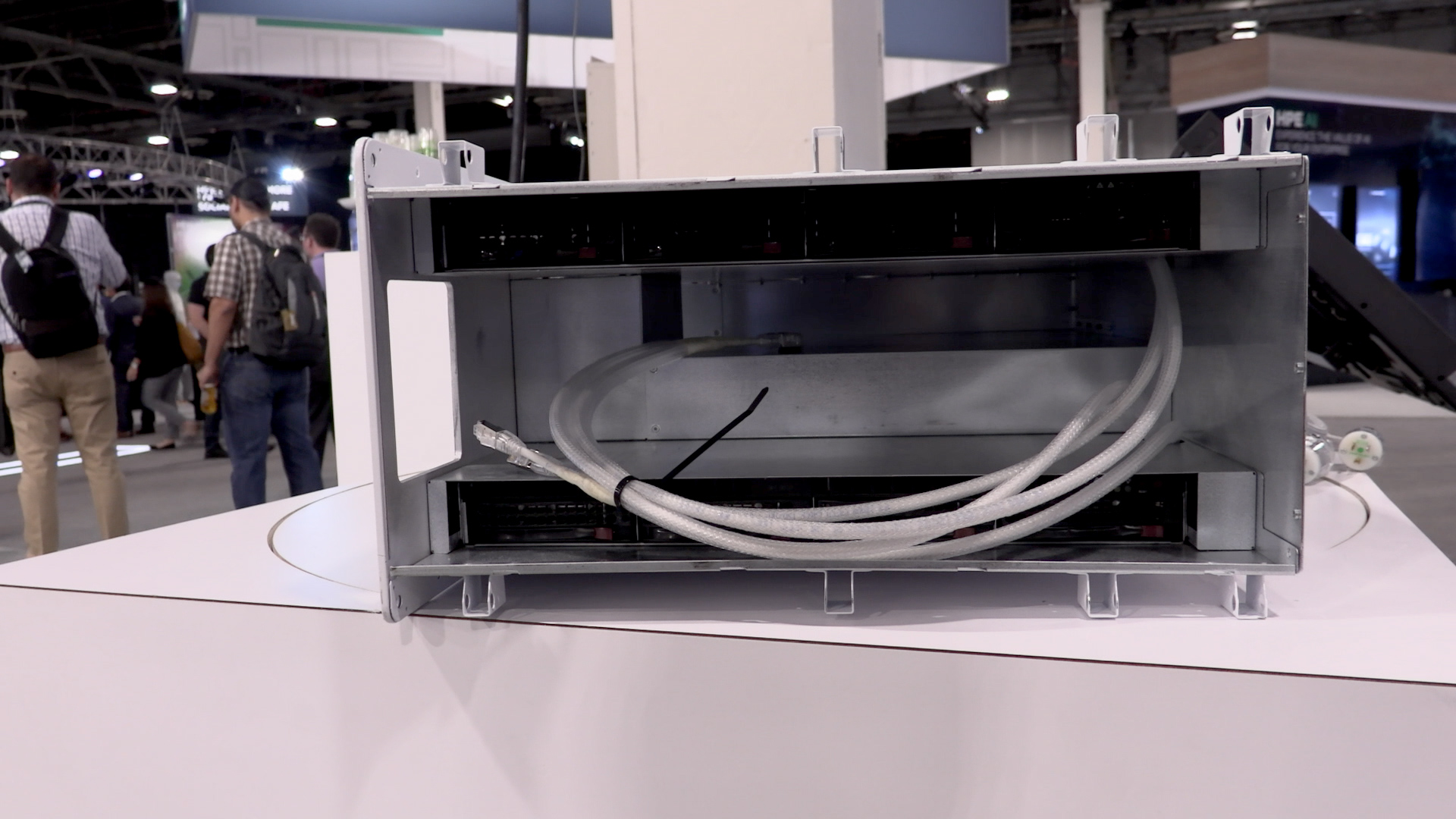

This is the front of the unit. Apologies for how dark it was. This was before I traveled with lights. HPE told me that the unit had to be designed to fit within the racks found on the International Space Station which was a particular challenge. Not only did the servers need to withstand the launch process, but once onboard, they needed to function within the existing infrastructure.

One can also see what may be some of the most expensive network cables to ship to their destination data center.

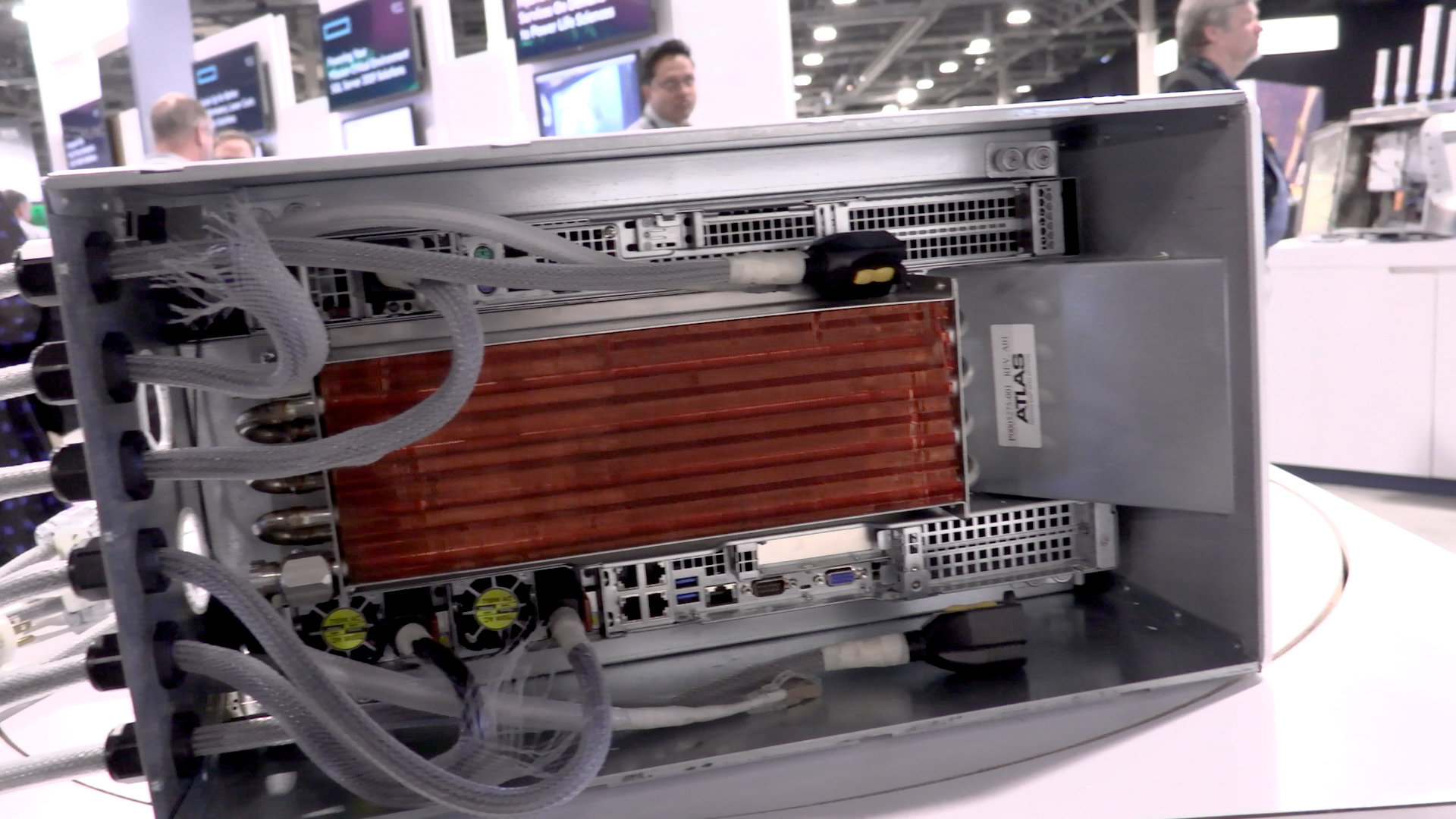

Something our keen readers will notice is that the systems on top and bottom are Supermicro 1U servers. This project was conceived at SGI prior to it becoming part of HPE. SGI used many Supermicro servers. My sense is that there was part of this that was lead/ development/ qualification time dependent. My other sense is that given this was an experiment, had they failed, HPE could have simply said that the servers were made by someone else. The switching one may assume was HPE’s but is clearly not present. I do not think it has been disclosed publicly, and I was told HPE was not allowed to show off the switches which is why they are removed. I can report that nobody explicitly said that a Mellanox switch was used so it is still a detail shrouded in secrecy.

On the rear of the unit, you can see a large heat exchanger. I was told that power for the unit is “inexpensive” since it is solar so one needs to simply fit within a power budget. Space is a cold place so engineers can utilize the ISS’s heat exchangers to keep equipment cool. In a normal data center, you may feel airflow from a cool aisle to the hot aisle. Here the hot aisle is effectively the heat being dumped into a heat exchanger that uses the relatively cold outer space environment to keep the system cool. A bad design is to vent ISS air to the back of the server and into the vacuum of space.

Overall, the solution was in space for 615 days. The impact of the first Spaceborne mission is that it proved that commercial off-the-shelf servers can be used in space. This is important since it drastically lowers the cost of procuring hardware to be used in space. It also shortens development cycles which means more modern and faster processing can be used in space than traditional hardened silicon.

The major challenges were in terms of NAND and DRAM reliability in space, but on the computation side, the goal was to create software solutions to check for errors due to cosmic radiation and use software to fix what had been traditionally a challenge solved with custom hardware.

Those learnings bring us to HPE Spaceborne Computer-2.

HPE Spaceborne Computer-2

HPE is launching its second effort dubbed “Spaceborne Computer-2” to the ISS as an update to the first platform. There are certainly some changes such as the 120V power being swapped for native power (I believe this is 28V DC) without the AC conversion.

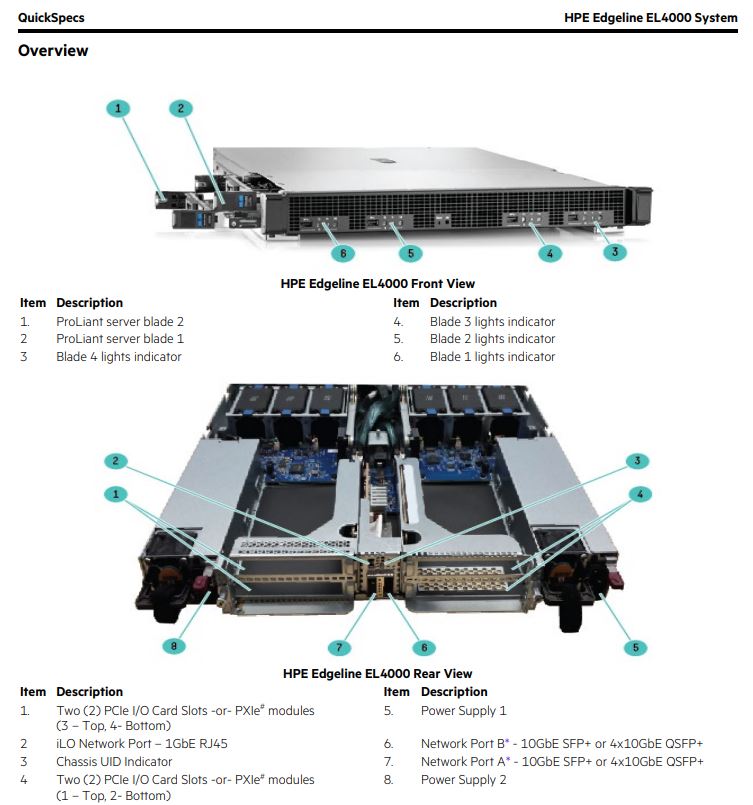

HPE also said that it will be using GPUs and its EdgeLine 4000 systems. The EdgeLine 4000 takes cartridges, somewhat akin to what we saw with Moonshot (apologies, I had to get that reference in) but also has room for PCIe expansion presumably used for the GPUs.

One of the interesting features is that HPE is teaming up with its close partner Microsoft to allow for Azure services to be connected. One can get burst capacity by sending workloads to the Azure cloud.

Final Words

We are in a window where a number of missions to Mars are reaching their destination which has around an 11-minute communication latency. While the ISS is still close enough to Earth to get regular communication, and Microsoft Azure cloud access, increasing computing capacity in space is a big deal. More processing power and AI acceleration mean that those building what will need to be autonomous systems due to communications latencies can use more modern hardware than traditional hardened processors. For some sense of what can happen in only a fraction of the 11-minute communications delay to Mars, here is a video animation of what NASA hopes will happen on 18 February 2021 when its Perseverance rover is set to attempt landing on the planet.

That video and contemplating what can go wrong and how AI could be used one day to autonomously guide the process is a fairly stark example of why the HPE Spaceborne project is an important one beyond being a great PR vehicle.

One remark: to have off-the-shelf hardware on ISS is still fine due to protection by Van Allen radiation belts: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Van_Allen_radiation_belt. The outer-space is way much harsher environment so not sure if we will see commodity x86 server(s) on Mars mission. I would guess this is still domain of RAD5500, LEON and NOEL-V chips.

> that uses the relatively cold outer space environment to keep the system cool

It’s not the cold space that is being used to shed heat from the ISS. :) It’s Black body radiation from the radiators that is being used to keep the ISS cool. Whether space is hot or cold doesn’t matter and has not bearing on the black body radiation, what matters is that the energy emitted via photons by the radiators is (much) larger than the amount of energy absorbed by photons hitting the radiators. Thus, don’t let the radiators face the Sun, otherwise your cooler turns into a heater…

Hmm… as an afterthought to my previous comment, that makes me wonder: Do some systems on the ISS utilize sublimation cooling? (Also, don’t let the radiators face the Earth either. Earth is a pretty planet, but it is also a relatively good reflector of sun light…)

Hello,

I realize this is very much a niche/specialized use-case device, however, I am wondering if HPE will be offering Foundation Care service or Proactive Care service with this model and, if so, were launch vehicle costs for inserting a service technician into orbit (and successfully recovering them) covered under contract or there were hidden fees for this sort of thing.

Regards,

Aryeh Goretsky