ChatGPT is something we have used over the past few months, mostly as a fun experiment. We have heard that the NVIDIA A100’s are being used for that. Many folks are using ChatGPT that have never seen or used a NVIDIA A100. That makes sense since they are often priced at $10,000+ each, and so getting an 8x NVIDIA A100 system starts around $100,000 at the lower end. We figured it would be worth a second to run through the STH archives and show you what the NVIDIA A100 looks like.

ChatGPT Hardware a Look at 8x NVIDIA A100 Powering the Tool

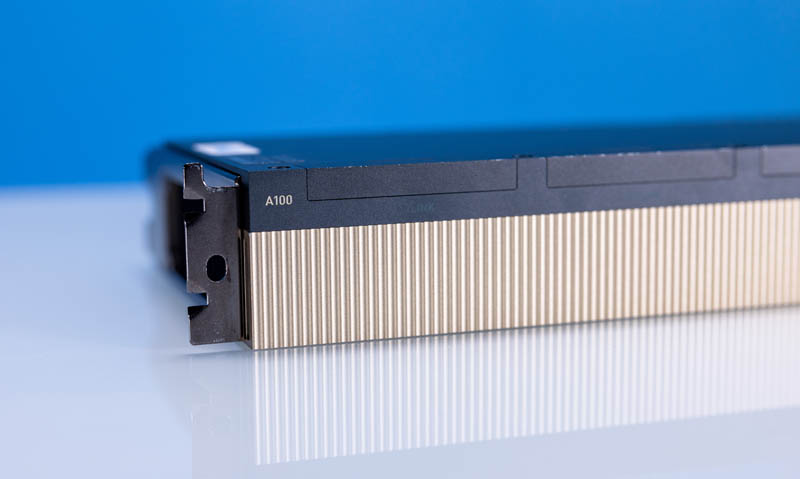

First, what is a NVIDIA A100 anyway? Many folks understand the concept of a GPU since it is a common component in desktop systems. Usually, GPUs are PCIe cards and can be used for gaming or has become more common in servers. NVIDIA makes A100 GPUs specifically for these types of systems.

There are a few differences between the NVIDIA A100 and NVIDIA’s GeForce series commonly found in gaming. For one, the NVIDIA A100 is designed with server cooling in mind. That means there are no fans and they are designed to be packed densely into tight systems.

While the GPUs have high-speed interconnects, called NVLink even in this PCIe form factor, these are not GPUs meant for gaming. The A100 is specifically tuned toward AI and high-performance computation instead of rendering 3D frames quickly for gaming.

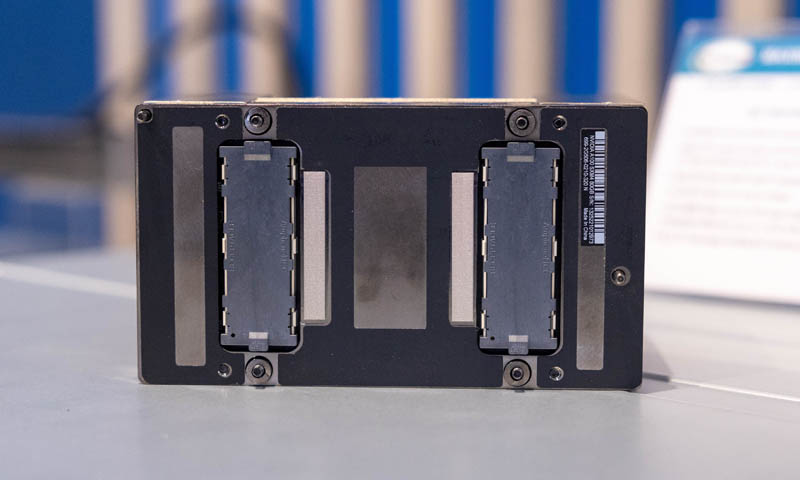

A great example of why this is the case can be seen on the back of the NVIDIA A100 GPUs. Here, the bracket simply has an exhaust for cooling airflow. These do not have display outputs to connect a monitor or TV.

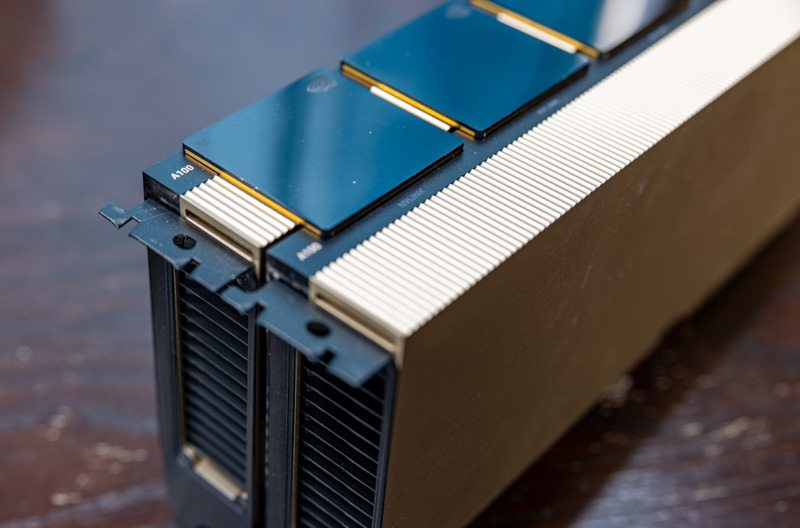

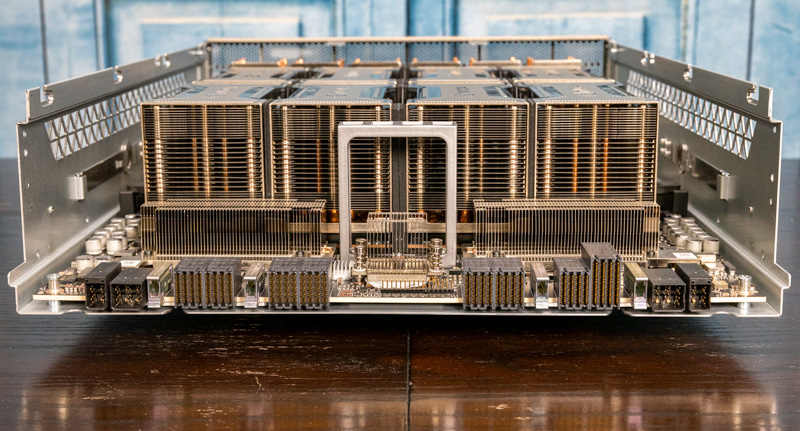

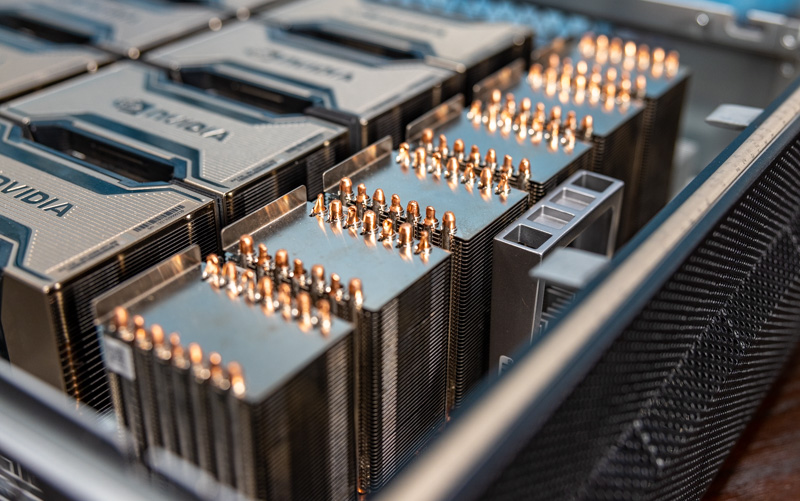

Most 8x NVIDIA A100 systems, especially at larger cloud service providers, use a special NVIDIA-only form factor called SXM4. In the picture below, the GPU is around the black layer near the bottom of the assembly. Over 80% of this assembly is a heatsink to dissipate massive heat. While the PCIe variants that look like gaming GPUs above are usually only able to handle 250W-300W, the SXM4 variants handle 400-500W each. That extra power allows for more performance per A100.

Each of these SXM4 A100’s is not sold as a single unit. Instead, they are sold in either 4 or 8 GPU subsystems because of how challenging the SXM installation is. The caps below each hide a sea of electrical pins. One bent pin, or even tightening the heatsink onto the GPU too tight, can destroy a GPU that costs as much as a car.

The last ones we installed ourselves required a $350+ torque screwdriver to hit the tolerances we needed. You can find that old STH video here with the old P100 generation (wow this is an OLD one!):

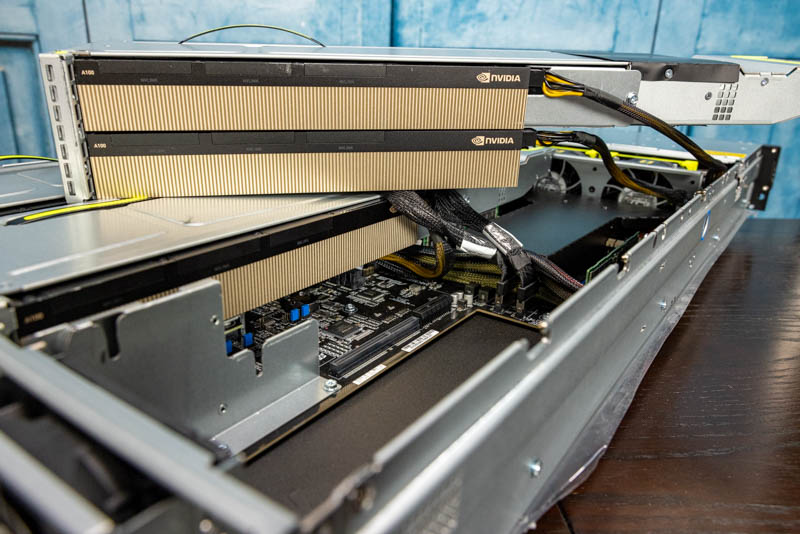

In modern servers, these are installed with 8x SXM4 GPUs onto a baseboard called the NVIDIA HGX A100. Vendors such as Inspur, Supermicro, Quanta, and others then use this HGX A100 as the cornerstone of their own AI systems. These systems are so specialized that Dell EMC did not even start selling them until very recently with the Dell PowerEdge XE9680.

Each baseboard is designed to align eight of the NVIDIA A100 SXM4 GPUs into an array. PCIe connectivity is provided back to the host server using high-density edge connectors.

The other large heatsinks on the NVIDIA HGX A100 are to cool the NVSwitches. NVIDIA has its own high-speed interconnect that allows each A100 to talk to each other within a system at extremely high speeds.

In a server, here is what 8x NVIDIA A100 80GB 500W GPUs look like from a NVIDIA HGX A100 assembly above.

That means that a system with these will be very fast but can also use upwards of 5kW of power.

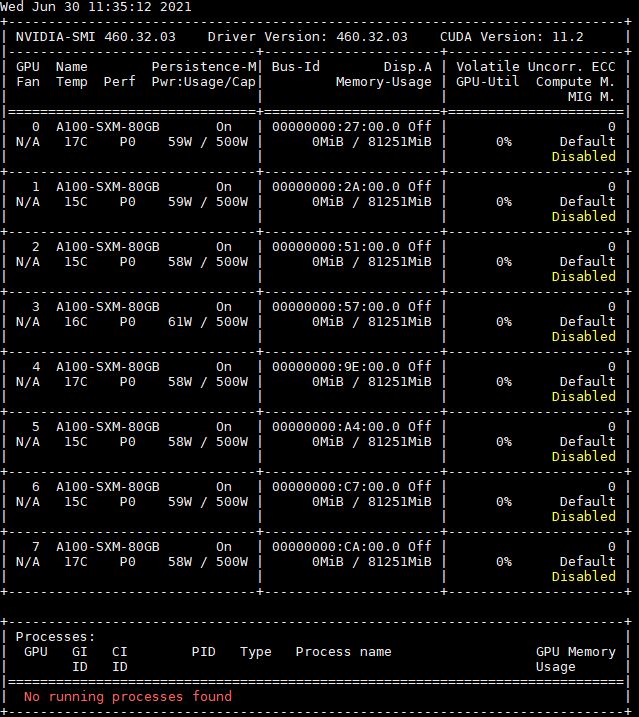

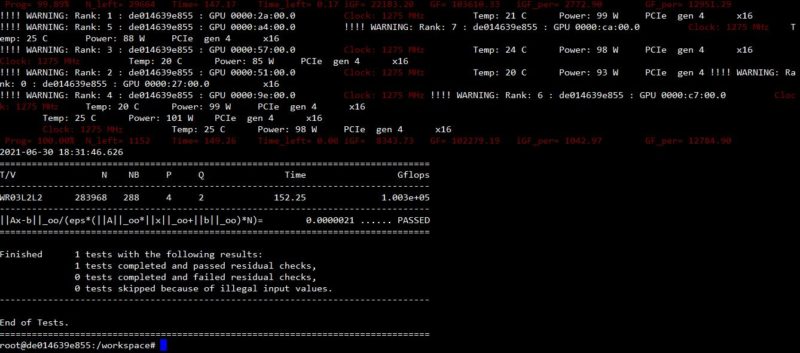

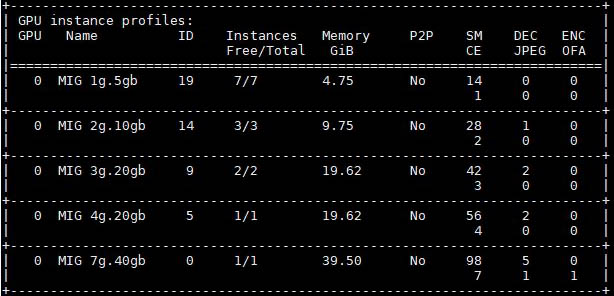

Since the NVIDIA A100’s have more memory onboard than most desktops and laptops, 40GB-80GB, and so much compute capacity, the NVIDIA A100 has a feature called many-instance GPU or MIG that can partition the GPU in different sizes, similar to a cloud instance. Many times, for AI inference, this can be used to run workloads in parallel on a GPU, thus increasing the throughput of a GPU to handle AI inference tasks.

Here is what happens when we split a 40GB NVIDIA A100 into two MIG instances.

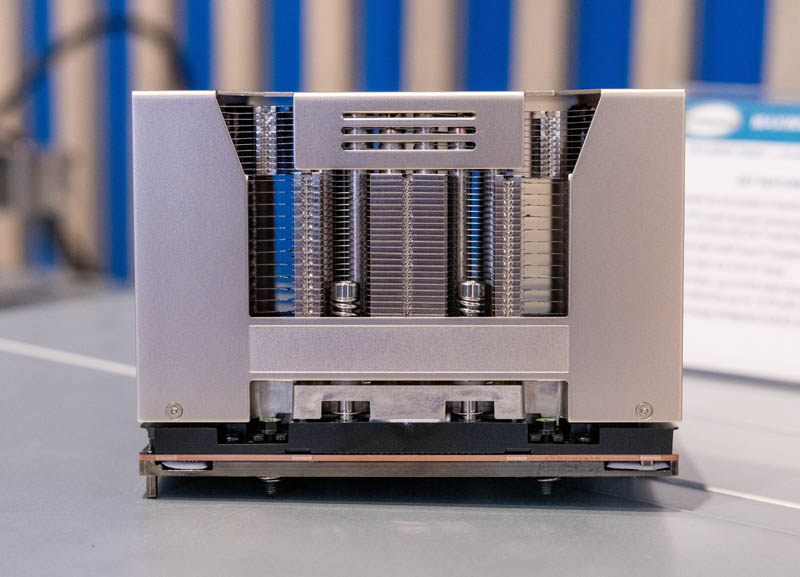

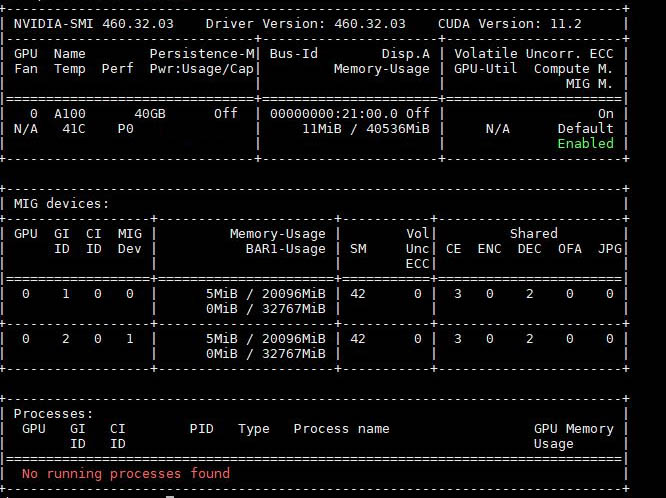

As you may have seen, all of this requires a LOT of cooling. Here are two NVIDIA A100 systems, the top is air-cooled, the bottom is liquid-cooled.

The liquid cooling increases performance and allowed us to run the A100’s at higher power limits, thus increasing performance.

We also did a deep dive on an A100 server in this video:

While the NVIDIA A100 is cool, the next frontier is the NVIDIA H100 which promises even more performance.

What is Next? The NVIDIA H100

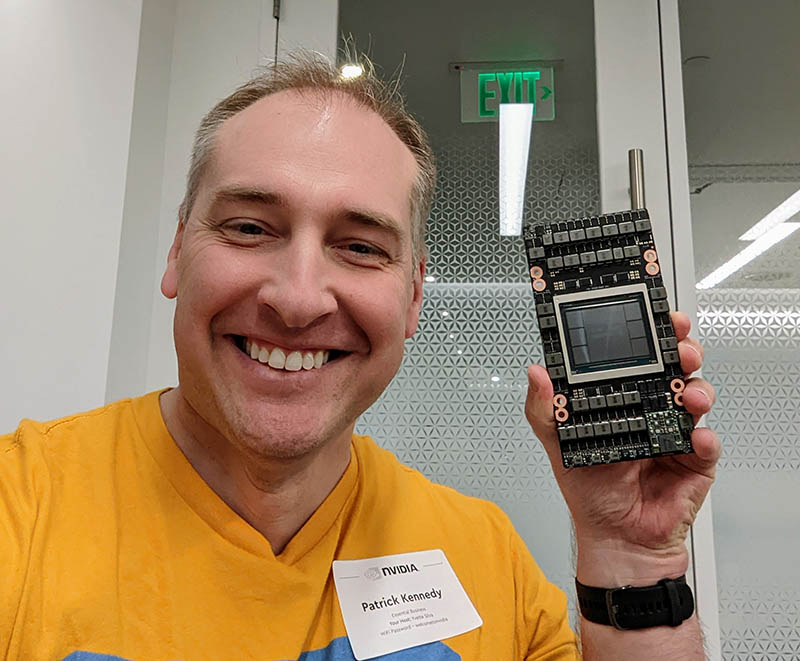

The next-generation part after the NVIDIA A100 is the NVIDIA H100. This is a higher-power card with the company’s new “Hopper” architecture. NVIDIA will have both PCIe and SXM5 variants. Here is the SXM5 H100 without its heatsink at NVIDIA HQ.

If you want to see the new NVIDIA H100 systems, we showed them off in our recent Supermicro X13 launch video:

We even had the NVIDIA H100 8x GPU systems, PCIe systems, and a desktop PCIe A100 system with massive liquid cooling in the GPU accelerated systems video.

We still do not have these in our lab since they are very highly demanded-products.

Final Words

Regular readers of STH have seen probably a dozen reviews of systems with the NVIDIA A100. Since the NVIDIA A100 is a hot topic given the OpenAI ChatGPT and now the Microsoft Bing integration, we thought it was worthwhile to show folks what these cards are. While the NVIDIA A100 and new H100 are called “GPUs” and may be more expensive than their desktop gaming brethren like the NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090, they are really high-performance computing accelerators tuned for AI workloads.

As always, stay tuned to STH for more A100 and H100 system reviews.

Torque wrench, U$80: https://www.firstinfo.com.tw/product-14(6-35mm)-Hex–Dr–Mini-Torque-Screwdriver-0-05-0-6Nm-H5177.html – $350 is a lot, we are not NASA: https://space.stackexchange.com/a/22190

Rob – the issue is the tolerance. The SXM GPUs have such tight tolerances that the +/- values can be outside of the range of what the GPU can handle. That leads to cracked GPUs. This is why NVIDIA does not sell A100/H100 SXM GPUs, only Delta (8x GPU) and Redstone (4x GPU) assemblies.

I had the pleasure of setting up and using a 12 node 8×A100/80 cluster. Going back to “normal” software development makes me yearn for the power. Software, including Kubeflow, and Wandb really ties the system together.

There is no cooling paste involved?

Ed – Typically, in servers, thermal paste is pre-screened on heatsinks. For SXM GPUs, if the paste is too thick, it will actually crack the exposed GPU chips. A top 3 server OEM screened slightly too much and that took out many V100’s back in the day. Now these are sold pre-assembled into larger assemblies so that and the torque variance are less of an issue. Still, even on the server CPU space, 99%+ of servers deployed do not have people applying their own paste. With the SXM GPUs, it is even less just because of how many have been cracked back in the P100/V100 generations.

How is it done with OAM parts such as the AMD Instinct or Intel GPU Max? Do they tend to be factory installed? If so are people commonly going to swap out one set of OAM parts from one manufacturer for another set from a different manufacturer on the same carrier board? What is the practical benefit for the extra hoop to jump through? Perhaps if you’re a chip designer designing a new product line it saves money by not needing to specify that part? Or you just might as well glom onto what already is available because there’s little advantage not to? Is “an open infrastructure for interoperable OAMs” actually taken advantage of practically?

How long before us humans are completely obsolete?