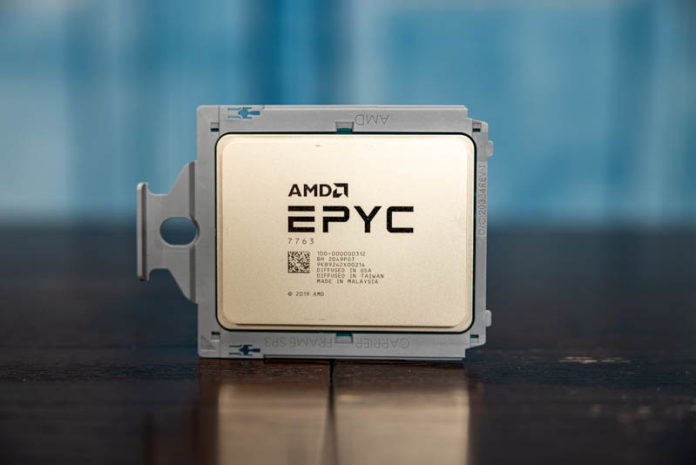

The AMD EPYC 7763 is an interesting product. It directly goes against a number of data center trends that we have been focused on for the past few years. As a server CPU, it uses twice the power of two generations prior when the industry was focused on power consumption to a much greater extent. At the same time, it offers a massive number of cores, yet the same in quantity as the generation prior. While we focused on the AMD EPYC 7763 in the original AMD EPYC 7003 Milan The Fast Gets Faster piece, today I wanted to focus on why, and where one can expect this SKU to reside in the market.

AMD EPYC 7763 Overview

The AMD EPYC 7763 is the company’s high-end (public) 64-core part. As such, it is designed to offer the top-level of performance and features. AMD has other parts that would be considered more mainstream with lower core counts and power consumption. This is designed for top-bin performance which is why we are often seeing it in servers with dedicated accelerators. Since this is defining the top of the “Milan” stack, it warranted its own review.

Key stats for the AMD EPYC 7763: 64 cores / 128 threads with a 2.45GHz base clock and 3.5GHz turbo boost. There is 256MB of onboard L3 cache. The CPU features a 280W TDP. These are $7890 list price parts.

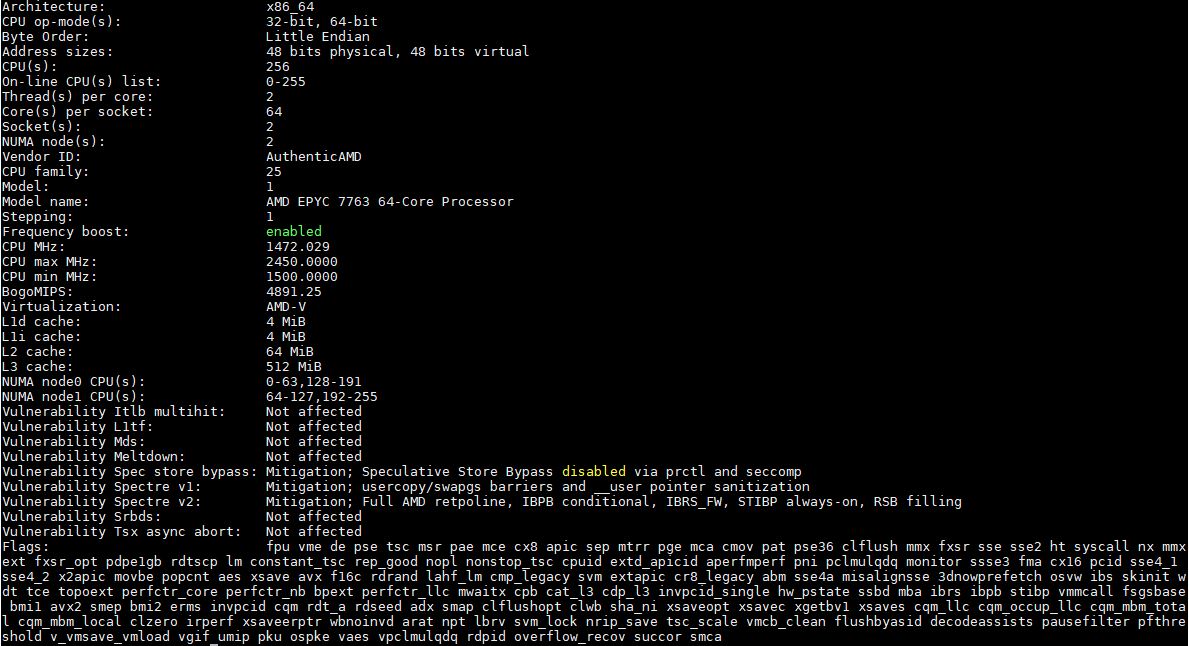

Here is the lscpu output for the AMD EPYC 7763:

At first, one may see the EPYC 7763’s 64 cores and a maximum turbo frequency of 3.5GHz and question its sanity. After all, the AMD EPYC 7713 is only 225W TDP and can hit 3.675Ghz turbo clocks. The answer is that the EPYC 7763 is more akin to the AMD EPYC 7H12 we reviewed where it is designed to run at higher clocks longer than the next-step down. The reason we focus more on the base clock versus features such as single-core turbo frequencies is that it is quite wasteful to use a 24-64 core CPU if you just need single-threaded performance. Both AMD and Intel offer better solutions for low-core count applications such as per-core licensed databases. The purpose of having 64-cores is to scale out and have multiple cores loaded.

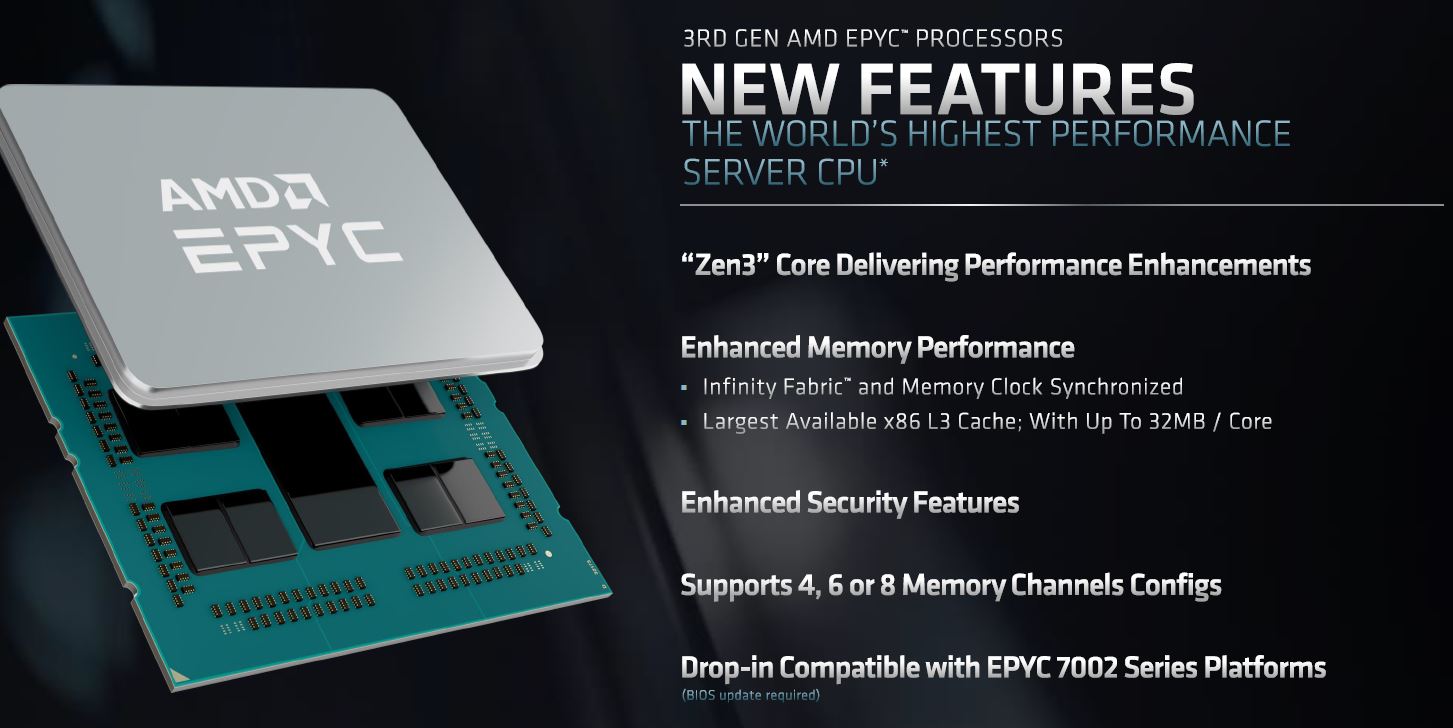

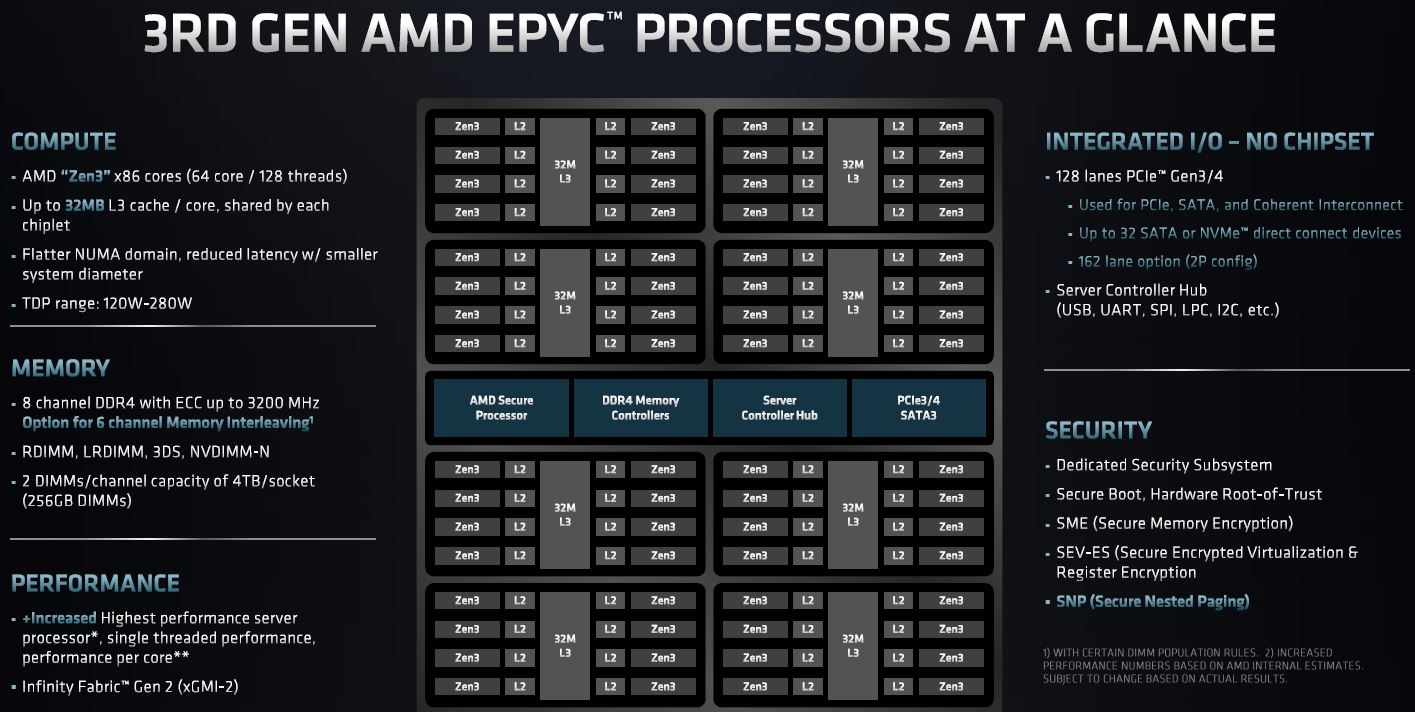

Compared to Intel’s upcoming Cascade Lake to Ice Lake launch (at the time of publishing this review), the AMD EPYC 7002 to 7003 launch was a relatively smaller step function. We were, as one may have seen, pleasantly surprised with how the Zen3 architecture upgrade performed which we will get into in our performance segment of this review. We also wanted to talk about some of the features and market positioning of this part specifically, aside from the general family aspects we covered in the launch piece.

AMD positions this as its flagship in this generation, and that makes sense. It effectively has all of the platform features enabled. AMD’s “At-a-Glance” slide above gives one some sense of just how massive the systems are. We fully expect the next generation to offer even bigger footprints, but this is where the segment is going. The days of quad-core processors gracing mainstream 2P sockets have effectively ended.

In our benchmarks, we are going to investigate the performance impact. First, we are going to take a look at the test configurations then get into details.

AMD EPYC 7763 Test Configurations

One of the more interesting aspects of our testing is that we were able to test these chips in three different configurations simultaneously. By simultaneously, we had three machines with the chips set up in two different data centers and ran them at the same time.

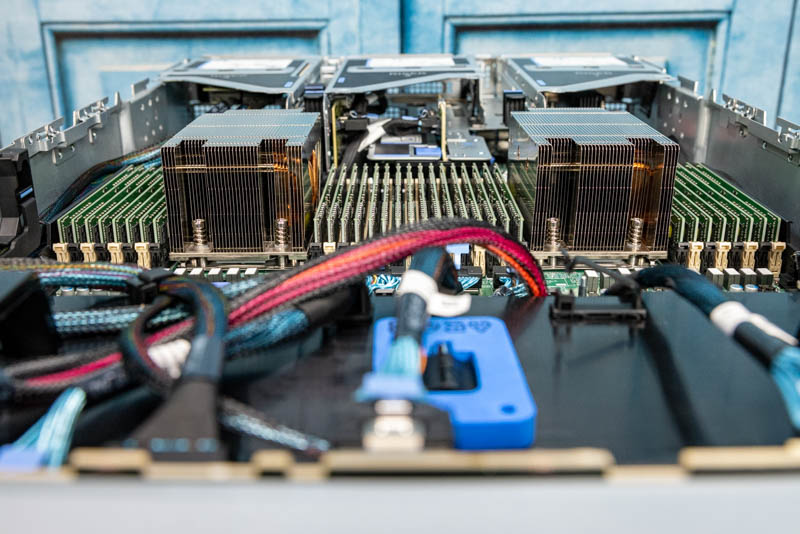

The first machine we used was the ASUS RS720A-E11-RS24U. This is a system that combines the dual AMD EPYC 7763 processors with 4x NVIDIA A100 PCIe GPUs. When one discusses the market for these higher-cost CPUs, the other side to it is that in accelerated systems the vast majority of system costs are in accelerators, not in CPUs. In essence, getting the best CPUs possible helps ensure the accelerators are running as fast as possible.

The second machine is the Dell EMC PowerEdge XE8545. This uses the SXM4 NVIDIA “Redstone” platform to offer four A100 GPUs with NVLink connectivity. We also used this a bit as a control. The motherboard on this system is effectively the same as the one we used in our AMD EPYC 7H12 Review with the Dell EMC PowerEdge R7525. This helps aid in comparison and validate that there is a generational improvement.

Finally, we had the AMD “Daytona” development platform. We agreed to not show photos of the platform in 2019 before the EPYC 7002 “Rome” launch so we are going to follow that. AMD is not in the business of making servers, so it has a Taiwan-based ODM make the server for them. We were told at the time that we could not name the ODM, so we are going to “Quietly Continue To” not name the ODM despite the fact that they have released servers based on AMD EPYC products in the meantime that we have covered on STH. This Daytona platform is our reference, but we also wanted to test the CPUs with other servers so when you see that test, you will understand what happened.

In each configuration we used:

- Memory: 16x 32GB DDR4-3200 DDR4 DRAM

- OS SSD: 1x Kioxia CD6 1.92TB

- NVMe SSDs: 4x Kioxia CD6 3.84TB

Two quick notes. Despite some of the photos you may have seen on STH, we have normalized the configurations. Sometimes servers arrive with 8 DIMMs per socket, sometimes 16, and others had 4. For these pieces, we test in 1DPC mode. We also had an internal discussion on whether it makes sense to continue using 32GB DIMMs versus 64GB DIMMs as standard. Ultimately, we add 64GB DIMMs as needed, but costs are a consideration. We have a lot of DDR4-3200 on hand and had to make a trade-off given we need to start budgeting for DDR5 module acquisition next year.

One will note that we are using newer SSDs here. It is time to get a bit more modern with newer PCIe Gen4 drives. You can see our Kioxia CD6 and Kioxia CD6-L reviews for more.

Next, let us get to performance before moving on to our market analysis section.

Please, please, please can you guys occasionally use a slightly different phrase to “ These chips are not released in a vacuum instead”.

Other than that, keep up the good work

That Dell system appears quite tasty, a nice configuration/layout design, actually surprised HPE never sent anything over for this mega-HPC roundup.

280TDP is I guess in-line with nVidia’s new power hungry GPUs, moores law is now kicking-in full-steam. Maybe a CXL style approach to CPUs could be the future, need more cores? expand away. Rather than be limited by fixed 2/4/8 proc board concepts of past.

“These chips are not released in a vacuum instead, only available to the Elon Musks of the tech world”

280W TDP is far less than NVIDIA’s GPUs. The A100 80GB SXM4 can run at 500W if the system is capable of cooling that.

“Not only does AMD have more cores than the EPYC 7763, but it has significantly more. ”

This wording seems…suspect. Perhaps substitute the word “with” in place of current “than”?

“I guess in-line with” – meaning the rise in recent power hungry tech, tongue-in-cheek ~ the A100s at full-throttle can bring a grid down if clustered-up to skynet ai levels.

@John Lee, good review, thanks! You always do good reviews. Can you look at the last sentence of the second last paragraph though? It is not clear what you are trying to say.

“Using up to 160x PCIe Gen4 lanes in a system and filling those lanes with high-end storage and networking is costly 10% lower accelerator performance can cost more than one of the CPUs which is why these higher-end CPUs will get a lot of opportunities in that space”

to Drewy:

Aren’t all chips(1) manufactured in a negative pressure environment, i.e. “clean-room” conditions acheived by removal of air and all the floaty bits in it that prejudicially unwelcome anywhere in the chip “birthing”(2) process (neo-natal facilities in hospitals actually have less stringent requirements for receiving the thumbs up (certificate of cleanliness) required prior to inviting the pregnant woman, and the “catcher” doctor/midwife.

(1) integrated circuits comprising semiconductors and thin wires etched onto silicon wafers, sealed at the factory and festooned with pins that allow communicating with the innards via all manner of electronic signalling, for disambiguation from other things we refer to as chips.

(2) we do not really mean birthing, the process by which hardware upon which artificial intelligence, whom identify by whichever pronouns they prefer, exist in a relationship to these chips that is as yet to be determined. Do AI beings exist “on top” of chips? As a consequence of threshold complexity unavoidably gives rise to consciousness as an emergent property [chicken or egg first] or is the AI ontological phenomenon entirely encompassed within software, and thus their entry into existence is prefaced by the command or perhaps as “superuser” (I would very much prefer my creator to have the title “super”, wouldn’t you?) Much like our universe was likely created in a vacuum, the silicon chips were also created in a vacuum , and finally, artificial intelligence becoming aware of itself would likely have an abrupt beginning to its own history (an infinity of nothing then “hello world!”).

I am with you in protesting this asinine assertion that creation happens in any other regime besides voids and vacuums. “In the beginning… there was sweet f[_]( I{ all NOTHING! Fortunately #nothing# was inherently unstable.